By Emily South (and Kate Khair – contributing author)

Are we seeing the patient’s world as clearly as we possibly can? Will a more complete picture help us to build better brands?

In business, making assumptions can be an important first step to solving problems. But it can also bias us in how we frame the challenges, the questions we ask, and the decisions we make. It’s the same for healthcare market research and pharmaceutical interactions.

The way we think about individuals living with illness, and how we design research and create solutions can be led by our own biases and assumptions about people. For example, as stated by Lorraine M. Thirsk ( 2014 ): “The focus on ‘self’ in ‘self-management’ can lead us to think about chronic diseases as a largely independent activity and that people require individual solutions.”

In addition, the word ‘management’ implies there is a set of strategies that everyone can work with consistently and effectively.

When designing research methodologies, we tend to zoom in on the main characters to learn about their experiences; the person living with the illness, the physician…maybe even the carer or the nurse.

And when understanding prescribing behaviours, we focus in on the physician-patient consultation. But what if this ‘individual focus’ is not telling us the whole story? Do we miss out on a valuable part of the story? Are the missing pieces key to the research objectives or to the brand we are helping to build?

An individual focus may not be accurate. Chronic diseases can be viewed in a more connected sense, “embedded in family, community and societal conditions that shape and influence” (Kendall, 2010).

Furthermore (paraphrasing Fritz Heider), we are all unreliable witnesses of our own behaviour. This is complicated further with the emotional burden for people living with an illness, impacting what they are able to recall and sharing with us only what they believe we want to hear.

Challenging an ‘island view’

At THE PLANNING SHOP, we have been conducting research to challenge what we call an ‘island view’ of the patient, by introducing ‘witnesses’ to our studies.

These are the people who are usually absent from research, but who have an important perspective and can potentially influence management and treatment. Taking severe haemophilia as an example, we recently completed a piece of UK qualitative research to see if ‘witnesses’ add value to patient research. We included witnesses to help us build a more complete picture and uncover deeper insights that we believe can lead to more effective brand building.

From the outset we chose a more open approach to the study, enabling us to include a wider range of roles – clinical and non-clinical – who we would not normally speak with. The recruitment process involved:

- Mapping all potential touchpoints of a person living with haemophilia (people considered to be in their team)

- Use of descriptive statements in the screening materials to describe the potential influence and involvement of ‘witnesses’ as well as the ‘main character’ roles

- Inclusion of a diverse sample of individuals viewing the haemophilia experience from different angles.

Our methodology included the use of indirect questioning, self-discovery exercises and challenging different team members with different viewpoints. We explored the most important connections and relationships with remote and live in-home discussions to build both depth and breadth of understanding.

Before we move onto the research outcomes, let’s talk haemophilia. What is it?

Haemophilia: Invisible. Unpredictable. Malicious.

Haemophilia is a rare, usually inherited, genetic disorder that inhibits the blood’s ability to clot, with types A and B affecting different clotting factors. 2017 UK annual data shows 9,639 people (mostly males) living with haemophilia in total, with 2,295 severe cases. These numbers exclude female carriers who may also have symptoms, and the wider sphere of different family and friends for whom haemophilia impacts.

Haemophilia can be described as:

Invisible: bleeding is the most identifiable sign, but it is often accompanied by chronic joint pain and psycho-social issues. The combined limitations and lack of wider community understanding can make haemophilia anti-social and isolating, lending a wider meaning to ‘invisible’

Unpredictable: even the most experienced person cannot always anticipate when or how haemophilia will strike; a repetitive task at work, a night out with friends, a simple knock at home or a trip on the pavement

Malicious: one day you might be busy with life, the next day you could be temporarily debilitated in a wheelchair, interrupting important plans and quality of life.

An underlying tension in the world of haemophilia

With treatment advances – such as selfadministered factor infusions – haemophilia care has moved from the hospital into the community. Comprehensive Care Centres (CCCs) with inhouse multi-disciplinary clinical teams including the haematologist, specialist nurse and physio (and psychologist in larger centres), are now providing hubs of expertise designing treatment and management plans, where people living with haemophilia can self-manage in the community and live their lives.

However, our research uncovered an underlying tension in haemophilia: living an independent life and self-growth, in a medicalised system. A tension which results in an ongoing risk-benefit gamble for patients and carers throughout their lives, with people asking themselves questions like:

- “Is it worth the risk of a bleed or chronic joint and pain issues?”

- “Shall I follow the rules?”

- “Who am I?”

Our research has shed light on how people living with haemophilia find their way around this tension.

Research outcomes

Insight one: Identity and tackling the lion

To begin to explain this tension we need to tell a story about Hercules.

Nemea the lion was a vicious monster in Greek mythology and Hercules had a huge task to conquer Nemea. After much persistence Hercules killed the lion with the force of his hands. Once dead, he removed the skin of the lion and used it like armour, making him invincible. In psychological terms, to fight the lion means to face our deepest fears, but to accept our weaknesses as part of our identity (wear the skin) is to be transformed.

Interestingly, the goal of being brave and wearing your haemophilia with pride is what the HCPs we spoke to try to inspire people living with haemophilia to do. Role models such as some patient influencers wear their haemophilia in a similar way. Take Christian L Harris for example, whose own severe haemophilia has inspired his fashion designs. Or Chris Bombardier who is raising awareness by completing the seven summits challenge with severe haemophilia.

But is this a realistic and desirable goal for all people with haemophilia?

We see there are different and overlapping paths taken by people living with the disorder:

– The regular guy: through adjustments and adaptions haemophilia is kept in the background and does not play a starring role. A sense of wellbeing and belonging is achieved

– Social withdrawal: on the journey towards being a ‘regular guy,’ patients can be derailed by the limitations placed on them by the disease leading to social withdrawal and isolation

– Low self-worth: their personal identity can be consumed by the negative associations of haemophilia and they can experience a loss of self-worth.

Those who have been affected by the contaminated blood crisis in the 1980s and blood borne viral illnesses may be particularly prone to the ‘cul-desacs’.

The paths for someone living with haemophilia are not consistent or straightforward, which lends value in understanding the perspective of ‘witnesses’ who accompany them in their world.

Insight two: The haemophilia team

The people with haemophilia in our research acknowledged that a team of individuals surrounds them. One person told us that he and his team collectively form “one functional person”. When observing the carer parent (typically Mums) and child team versus the adult team, we noticed that they are different in size. The parent and child teams tend to be large and varied. Adults have a smaller and intimate team. During clinical transition (from paediatric to adult care), teens and young adults leave behind what was their parents’ team and build their own trusted team from scratch.

Romantic partners or best friends are often the adult patient’s most influential team members – more so than the medical team. This team evolves over time through the course of different life events (e.g. relocating, marriage, having children etc). A partner or a best friend (unlike the medical team) can be confided in over the long-term, offering regular emotional and practical support.

Our research showed that the clinical team, however, perceived things differently. They acknowledged that the person living with haemophilia has a team surrounding them, but they over-estimated the influence of wider friends, immediate family and independent organisations or charities rather than the trusted team. How does this happen? People living with haemophilia stated how wider friends and immediate family “don’t get it,” organisations don’t offer valuable support locally, or they are comfortable with others not knowing too much because it creates too many questions and distractions from their everyday lives. There may also be geographical, cultural and religious reasons for people not being open about their health status.

Importantly, the clinical team over-estimated their own influence, believing they offer more emotional support than people with haemophilia think they do – sometimes under the guise of education.

There are three core reasons for these disconnects and tensions from a clinical perspective:

- The geographical distance of CCCs from people

living with haemophilia and their families and once or twice-yearly face to

face interactions with the clinical team

- The physician focus on clinical aspects: ‘blood

and joints’ and the assumption that haemophilia is ‘manageable’ for everybody

- Simultaneous trust and distrust: trust in medical expertise, but lack of trust in the medical team’s understanding of their lives and desires as a person.

The reality of living with haemophilia is complex. Patients surround themselves with a trusted network of individuals. Speaking with these team members is vital to understanding how people navigate their world with haemophilia.

The clinical perspective is not sufficient for understanding this. The most critical team members are a subset of all the witnesses we spoke to and represent a new target for research and brand building – the ‘Outside-In’.

Insight three: The unique perspective and influence of the ‘Outside-In’

The ‘Outside-In’ team members of the person living with haemophilia or parent carer:

- Are not necessarily part of the multi-disciplinary clinical team or part of family or friends

- Have come from the outside and are now on the inside, meaning they are able to give a fresh perspective on haemophilia (e.g. a new romantic partner)

- Know the person living with haemophilia or parental carer inside-out.

In our research we identified many examples of ‘Outside-In’ team members – these individuals are in a unique position to not only share their view of the person’s world and experience, but also to take an influential role and effect change.

An example of an ‘Outside-In’ team member who took part in our research is Sarah:

Sarah is the relatively new partner of John who lives with severe haemophilia. As part of the research we conducted in their home, the couple shared some interesting anecdotes:

- Sarah activates and augments John’s engagement with treatment. In discussions, John compared his adherence to treatment before and after they met:

“I know sometimes they [the bleeds] go untreated – I would say that’s quite rare now… 10% would get treated previously, and 10% might be left untreated this time round.”

- Sarah takes an ongoing role in monitoring and communicating John’s treatment via a haematology app called the Haemtrack app. John takes a more passive role. He said:

“I wouldn’t do that. I’d forget to be quite honest. So you’ve [Sarah] got it on your phone. I haven’t got it on my phone.”

Sarah also helps to filter information to John in a way she knows is digestible from sources online and by being an active member of the Haemophilia Society (unlike John).

- Haemophilia is not just about looking out for the immediate patient. It’s about future generations too. During discussions Sarah dropped the word ‘daughters’ into a conversation with John’s long-term haematologist. This was planned to have a domino effect. Sarah had previously recognised that John’s daughters from a past relationship were carriers of haemophilia. They all knew this, but there were no proactive conversations going on. John believed:

“It would have been on the [medical] record, but then it just gets lost.”

Sarah clarified that a conversation with the doctor would never have been prompted by John or his doctor without her and said:

“Because of my career (as a healthcare professional), I know what questions to ask… maybe nobody else would.”

As a direct result of Sarah’s intervention John’s daughters are now receiving adequate information on haemophilia and available treatments and can start to plan their own families.

Sarah’s anecdotes show that the ‘Outside-In’ are highly conscious of the person’s experience and are influential within their world. We identified many other individuals like this, clinical and non-clinical.

For example, a support worker who had a unique birds eye view of the multi-disciplinary team, and who also had a view of people who would never usually take part in market research, and a young man having social and housing issues who retreats to online gaming to actively avoid managing his haemophilia.

In summary the ‘Outside-In’:

- Create positive adjustments and adaptations to the person’s lifestyle

- Are highly engaged and influential in treatment and management

- Enable the people they care about to live in the moment rather than reflect negatively on the past or worry about the future.

Ultimately the ‘Outside-In’ are creating resilience and ongoing functional wellbeing – more complex than simply emotional or practical support. As time moves on they expect to have an increased role in the lives of the people they support with haemophilia.

We have picked out this specific group of individuals because they are significant influencers and could help us to piece together a more accurate picture of the patients’ experiences. Other team members were valuable to speak with as well – especially in collaboration with the person living with haemophilia. For example, where the individual with haemophilia wasn’t able to express themselves, the team member was able to fill in the gaps. Simply their presence in the conversation and acknowledgement of the issues led to more natural and collaborative discussions.

Importantly, by speaking with the ‘Outside-In’ and other team members, we were able to gain a more complete picture of the person’s experiences with haemophilia and understand how the important tensions in haemophilia mentioned earlier are currently being navigated, serving as a solid platform for communications and solutions generation.

Our findings raise important considerations for the clinical approach to haemophilia care in the UK National Health Service (NHS). The focus on independence and self-management doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality of what management in the community entails.

There is potentially a need to re-think how clinicians can support and engage in the person’s world via their haemophilia team (as long as privacy considerations allow). For example, adults who wish to bring their team into the relationship with the clinical team should be encouraged (not judged by the clinical team), because team members can add valuable insights impacting personalised treatment and management decisions. It is also important to note that there is a tipping point for new and innovative treatments – for example, will less need for hospital delivered care lead to more isolation for haemophiliacs?

Outcomes and ideas

Patient world

Brand engagement has come a long way since sales representative product messaging to physicians. We have started to acknowledge patients as engaged and influential people in treatment and management. It is now time to zoom out to reveal the world of the person – a wider web of social interactions and situations – a more complex system of decision influences and triggers. We believe this broader picture is currently an untapped resource of experiences and insights across therapy areas.

Solutions driven by the ‘Outside-In’

We have learned that the ‘Outside-In’ team have a transformational effect and are important influencers in the world of the person. We suggest brands tap into the problem-solving skills of the ‘Outside-In’ for solutions and ideas generation. As experts in the desires and quality of life of people who happen to have an illness, and with experience in creating lifestyle adjustments, the ‘Outside-In’ can help brands develop solutions that connect better, are more sustainable and work beyond an individual level.

Diverse brand engagement

Brands need to be able to engage with multiple team stakeholders and evolve tactics across life stages with channels and messages tailored to the right people at the right time. When services are being created, pharma brands need to be conscious of ‘connectability’ and input from wider team members. For example, brands can create campaigns like Alzheimer’s brands and charities that recognise the importance of the role of carers and families. This idea can be built upon even further; taking inspiration from consumer brands like Kraft and Premier Foods who are using insight gained from family, friends and communities to create campaigns and tactics that are tapping into the desire of connecting people together. One example is the Bisto ‘Together Project’, highlighting loneliness with their ‘Spare Chair Sunday’ project and bringing friends and family back together who have lost touch.

Communications through the lens of life

We encourage brands to create a new language to be more relatable. Patients are people living with an illness. Creating higher purpose and communicating through the lens of life will create stronger positionings and differentiation in crowded and clinically focused markets, ultimately building trust. This is whether it’s helping the clinical team to quickly understand the person’s context and desires in consultations to create tailored solutions or creating resources that move beyond educating about narrow medical moments to instead helping people to live their lives better.

It is a new era. We need to zoom out to understand the person’s world and experiences as clearly as we can. We need to understand all of the factors that influence them within their context. We need to use the ‘Outside-In’ to create valuable brands that speak to the people that use them.

About the authors

Emily South

Innovation Director

Emily South is Innovation Director at THE PLANNING SHOP. With a curiosity for people, stories and problem solving, Emily drives the development of new research approaches and tools for effective brand building.

Emily has a BSc Hons in Anatomy and Human Biology, and Biomedical Science from the University of Liverpool.

Kate Khair

Chair of the nurses’ committee of the World Federation of Haemophilia

Dr Kate Khair is chair of the nurses’ committee of the World Federation of Haemophilia and a leading specialist nurse in the UK, based at Great Ormond Street Hospital, London.

________________________________________

References

Kendall, P. (2010). Investing in Prevention: Improving Health and Creating Sustainability: the Provincial Health Officer’s Special Report. Office of the Provincial Health Officer, British Columbia.

Lorraine M. Thirsk, A. M. (2014, Maya What is the ‘self’ in chronic disease self-management? Retrieved from https:// www.journalofnursingstudies.com/article/S0020-7489(13)00283-6/fulltext

Download the pdf version here.

Jeremy Smith, Director of Client Strategy in the Oncology Research Group at The Planning Shop explores answers to these questions.

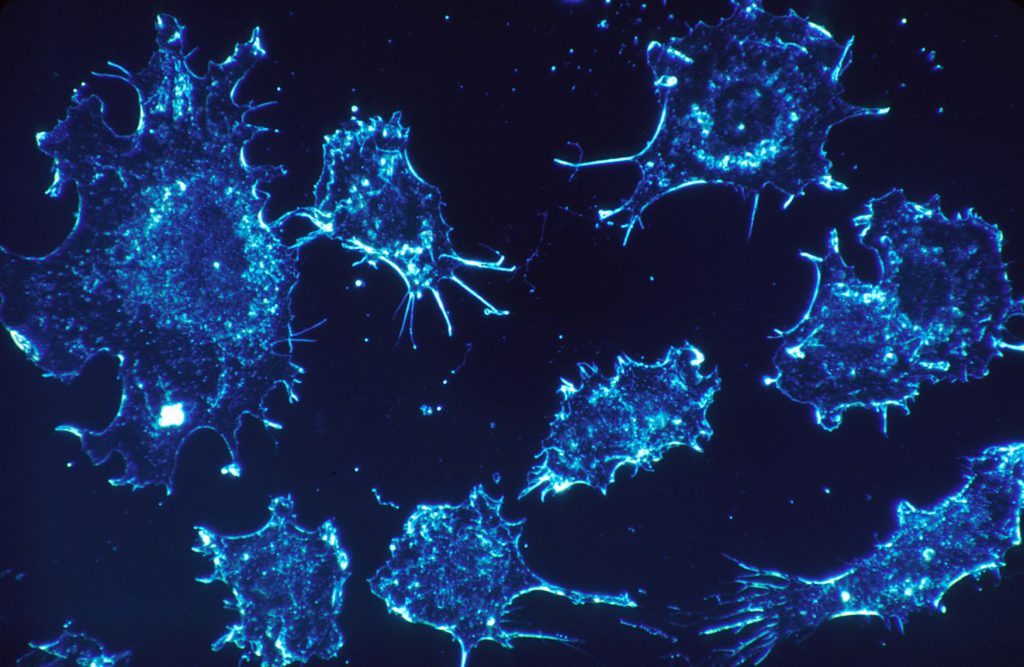

Cancer: One of the worst diagnoses a person can receive, which affects not just the patient, but also the wider family unit, caregivers and healthcare providers.

All these people play significant roles in trying to make the patient well, but how big should these roles be when it comes to decisions, and who should have the final say? Also, what are the implications for pharmaceutical market researchers?

Before we look at the role of each stakeholder, it’s important to highlight the significant advancements in the treatment of cancer – both in the treatments themselves and in patient/caregiver knowledge.

The past and the present

In the not-so-distant past the only treatment option for many cancer patients was systemic chemotherapy. More recently, immunotherapy has significantly changed how we treat a wide variety of malignancies. Nivolumab, the first FDA approved checkpoint inhibitor was initially approved for the treatment of Melanoma in 2014. Since then, checkpoint inhibitor approvals have exploded from several manufacturers in multiple tumor types.

Whilst the treatments themselves were advancing and immunotherapy has drastically changed the treatment options, so too were the education resources that were available and targeted to patients and caregivers. This has led to the evolution of the informed patient, which has drastically changed how treatment decisions are made.

How have patients become more informed?

Advertising

The first pharmaceutical television advertisement aired in 1983. That advertisement was for a prescription ibuprofen and was sponsored by Boots Pharmacy. Despite this early 1980s commercial, television advertising did not catch on until 1997 when the FDA ruled (after the 1996 Shering-

Plough Claritin television commercial) to relax the guidelines for television commercials. Television advertisement spending then jumped from $12 million per year in 1989 to $1.17 billion in 1998 and it has continued to increase ever since with spending in 2017 totaling $3.45 billion.

Although some question the ethics of pharmaceutical DTC advertising, there is no doubt that it has contributed to the increase of more informed patients and caregivers. Despite the marked increase in pharmaceutical DTC campaigns, there have been few television commercials for oncology treatments and, those that did exist, focused on supportive care rather than cancer treatments themselves. Still, the effectiveness of pharmaceutical advertising cannot be overstated. For example, prior to the Procrit DTC campaign, the drug – approved for certain types of anemia (which can cause patients to feel fatigued) – garnered little use because patients were not telling their doctors they were fatigued. The Procrit DTC campaign however, empowered patients to talk to their doctors about their fatigue which resulted in a significant increase in Procrit prescriptions.

Fast forward to 2018 and the number of oncology treatment television DTC campaigns are increasing as we see more and more advertisements for anti-cancer medications in the United States. Television campaigns currently include nivolumab, pembrolizumab and even reach beyond checkpoint inhibitors to include palbociclib and abemaciclib. These commercials are likely to be raising interest and awareness among patients and caregivers, causing them to do more research about their condition and possible treatment options.

Digital transformation

Beyond DTC advertising, and the availability of disease and treatment information, patients are increasingly able to take advantage of new technologies to access and monitor their own health information via online portals, wearable sensors and smartphone apps. As Eric Topol points out in his book ‘The Patient Will See You Now’, while we’re not fully at the point of the patient owning their medical records, the technology exists, and this reality may not be far off.

So, what does it all mean?

Ultimately, it means more informed patients and caregivers, with physicians no longer being the sole providers of medical and treatment information. Patients and family members are becoming self- educated about their malignancies and treatment options, resulting in all parties having strong ideas about the best treatment option.

Let’s look at a typical scenario

A newly diagnosed lung cancer patient goes into their oncologist’s office accompanied by their adult child.

The patient has seen the nivolumab and pembrolizumab television commercials and has completed extensive online research that has resulted in her believing that immunotherapy is the right choice for her because it provides a good chance for prolonged survival with minimal side effects.

The adult child, having completed similar research, believes that immunotherapy + chemotherapy is the right choice since it combines both treatment modalities and should, therefore, provide the best chance at survival.

The oncologist, utilizing all of his extensive medical training and experience, believes that standard chemotherapy is the best first choice in order to save immunotherapy for second line. In this scenario, who has the final say? What will the treatment choice be?

This answer will of course differ for each conversation, but it is safe to say the final decision will be mutually agreed upon. The oncologist would be remiss not to consider the patient’s wishes

and, most importantly, the reasons behind those desires. But similarly, the patient would be remiss to dismiss the wishes of their family and the extensive experience of the clinician.

What does this mean for pharmaceutical market researchers?

In the past, most pharmaceutical market research projects have been conducted around physicians, payers and KOLs with the patient perspective often relegated to a singular patient journey project. However, as treatment decisions are becoming increasingly more collaborative, it is important to include the patient and caregiver perspective in pharmaceutical market research projects to build stronger brands. Two key brand rules explain how this can be done.

1. ‘No problem, no brand’

Ultimately, the brand needs to solve a problem in order to be successful. By incorporating the patient and caregiver perspective, market researchers are better able to frame the problem that the brand will solve. Even if the overall plan does not include a DTC campaign, what better way to bring the problem to life than to incorporate the patient language and perspective?

2. ‘The truth, powerfully told’

The inclusion of the patient and caregiver perspective serves to strengthen the overall brand story. The underlying reason many HCPs enter medicine is to help people. How better to tell a powerful, motivating story than by incorporating the perspective of those patients who will be helped by the brand?

That’s great, but how do we do this?

It can be easier to include the patient perspective than one would think! Often times, KOLs are included at the start of a project in order to get the thought leader perspective on the future treatment landscape or the merits or a particular product.

Why not take a similar approach with patients and caregivers? Including a few patients and caregivers in order to get their perspective about the challenges of living with a condition or taking a particular medication can pay significant dividends. Even if the brand never plans for a DTC campaign, this additional insight will strengthen the HCP-directed communication materials. Imagine how much more powerful the HCP directed messages or concepts would be if they included the very language that they hear from the patients they are treating!

In conclusion

Traditionally, the incorporation of the patient perspective would mean a ‘patient journey’ project. While a traditional patient journey can certainly

be useful, in an age where patients are more knowledgeable and empowered, we suggest going beyond the traditional approach. Consider including patients and caregivers in other, typically HCP-only, projects as well. The patient/caregiver perspective should be incorporated when developing a positioning, identifying drivers and barriers to use, and creating physician directed messages, just to name a few.

About the author

Jeremy Smith, Director, Client Strategy

Jeremy has over 12 years of global pharmaceutical research experience, including over three years of exclusive oncology experience.

Download the pdf version here.

Jeremy Smith discusses the cost:benefit ratio of the rising prices of new oncology treatments and how the pharmaceutical industry and regulators can adequately address them while still promoting R&D.

Oncologists and pharmaceutical companies are increasingly discussing the cost:benefit ratio of cancer treatments. It is a topic that is under the microscope, particularly now, with the advent of immunotherapies. These come with a hefty price tag of approximately $100,000 per patient per year, compared to carboplatin + paclitaxel, a standard treatment for squamous cell Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), which could cost $30,000-$35,000.

Looking at the cost:benefit ratio of these treatments as a sliding scale, though, it could be argued that immunotherapies may fall more on the side of benefits (as opposed to cost). Because, although expensive, they are currently approved in malignancies where survival has been measured in months, not years, and the side effects during treatment can be less intrusive.

Conversely, many of the newer haematologic malignancy treatments are equally, if not more, expensive, but they are used to treat patients in diseases where survival is measured in years, not months. Nonetheless, and regardless of the type of malignancy, the treatments are resulting in financial toxicity for patients. So, what happens now? Let’s look at this debate in more detail.

Immunotherapy results for treating solid tumours

According to Cancer.org, the five-year survival rate for Stage IV NSCLC patients using traditional chemotherapy is less than 5%. Comparatively, if a patient is treated with nivolumab (an immunotherapy marketed as Opdivo), recentlypublished data, at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting 2017, show the treatment increasing the five-year survival rate for Stage IV NSCLC patients from 4% with standard of care (SOC) chemotherapy to 16% in all-comers (and 43% in patients with > 50% PD-L1 expression).

In addition to the improvement in survival rates, immunotherapies also produce fewer adverse events, which is likely to lead to better patient quality of life. This is no small consideration, especially when all treatment is ultimately only palliative. The benefits of immunotherapy can be huge – even if the costs are huge too.

If immunotherapy falls on the benefit side of cost:benefit scale, where should many of the new haematologic malignancy treatments sit? Unlike some solid tumour patients, many haematologic patients have survival rates measured in years, not months.

However, many of the newer haematologic malignancy treatments combine multiple (as many as four) different drugs. And, in a regimen where there are multiple branded products, this means the costs can be significantly higher than $100,000 per patient. Finally, not only are multiple branded medications needed, but the duration of therapy is often longer in haematologic malignancy treatments than in solid tumour treatments.

Yes, the five-year survival rate for all Multiple Myeloma patients is 49% – which is nearly three times that of all (not just Stage IV) NSCLC patients. And longer survival rates are a positive outcome. However, the treatment costs can be enormous.

Even though many of the new haematologic malignancy treatments are less expensive individually than immunotherapy agents, they still come with a hefty price. For example, elotuzumab, for a Multiple Myeloma patient weighing between 154 and 176 pounds, will cost $142,080 for the first year and $123,136 for each subsequent year. This is a huge cost in itself. But keep in mind that these costs are for elotuzumab alone, and the treatment often needs to be used in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, which adds an estimated cost of approximately $125,000 per year, bringing the total cost to $248,136 – $267,080 per patient, per year of treatment.

Elotuzumab increases the four-year progressionfree survival rate (when added to lenalidimide and dexamethasone) by 7%, from 14% to 21% for patients with 1-3 prior lines of therapy. However, elotuzumab is given until treatment progression, which means that those 21% of patients still responding at four years could end up spending $511,488 for elotuzumab alone.

New treatments in oncology – whether solid or haematologic – are producing better efficacy and improved tolerability. The benefits are immense. However, the price tags can lead to huge financial toxicity for patients.

So why are the treatments so expensive and how can the balance be redressed?

According to a 2014 study by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD), the estimated cost to develop a new prescription drug for marketing in the US is $2.6 billion. Compare this to a much lower figure of $800 million in 2003. Pharmaceutical companies need to pass their costs on, so we can see why the end price points to patients have risen. Pharmaceutical companies also want to develop new drugs and the revenue they receive from their marketed products is what finances this new drug development.

Regulators wish to simultaneously reduce costs to patients while continuing to encourage new drug discovery. It is a tricky problem. While many people would agree that financial toxicity can be debilitating, how to correct it is much more complicated.

Back to the cost:benefit ratio. What’s next?

All of these data points and costs are interesting but what does it all signify, and how should the cost:benefit of new treatments be evaluated?

Historically, a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival, regardless of solid or haematologic malignancy, has been enough to warrant regulatory approval. However, in June 2015, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) published a proposed framework, which it subsequently updated in May 2016, to assess the value of various cancer treatments with the goal of evaluating treatment regimens on the basis of their clinical benefit, toxicity, and cost.

Despite the fact that there have been no changes in pricing, reimbursement, or approvals as yet, and costs continue to rise, perhaps the approval authorities should be looking at different criteria – such as a certain percentage increase in efficacy (for example quality-adjusted life years and the value to patients and their families), not just statistical significance – to justify the higher costs.

As it is, there is anecdotal evidence that patients, particularly in the US, are already evaluating the cost:benefit of their prescribed oncology treatments and making their own decisions accordingly. A recent policy brief published by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy cites that the 8-to10-year survival rate for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) is 80% in Europe, where treatment is available and affordable to all patients. In the US, as a comparison, the high drug prices could force many patients to omit or compromise treatment, which reduces the five-year survival rate for CML to only 60%.

While most agree that some sort of pricing reform is needed, the underlying question is how to adequately address the astronomical prices while still promoting further research and development. And what impact should the current survival rates have on this evaluation? There is no easy answer, and these decisions have far-reaching implications. It is certainly something for everyone to scrutinise particularly as even more personalised treatments are produced. For example, CAR-T which is now approved and costs between $373,000 and $475,000 for each patient.

Impact on market research

The market research world often tries to decouple the financial impact from the clinical strengths and weaknesses of a treatment, in order to understand the drivers and barriers to use. As costs continue to rise, this not only becomes more difficult, but possibly also misleading. Even though oncologists sometimes claim to try not to consider costs when weighing treatment options, in order to recommend the best option, can they realistically be expected to ignore the fact that many of these treatments now cost more than double the average annual salary of their employed patients?

From the perspective of market researchers, in order to fully understand the likelihood to use one of these costly treatments, attention should be paid to the impact of cost, and the financial toxicity for patients.

The obvious answer is the inclusion of payers in the research plan to understand expected pricing, formulary tier, and patient out-of-pocket costs. However, it is probably not enough to stop there.

Oncologists are becoming more sensitive to cost so reserving a section of the discussion guide for a cost:benefit evaluation could also be beneficial. There, it would be possible to understand how oncologists balance the cost:benefit through a live perceptual mapping exercise and/or an explicit evaluation of price. For example, it could be beneficial to understand what percentage of patients would be likely to receive a given treatment at various price points. (There is a flip side to this, though – one that is controversial. As it is popular right now to mention costs even though it appears to currently have little impact on oncologists’ decisions and is not something they discuss with the patients unless specifically asked, since their ultimate goal is to provide their patient with the best available treatment.)

The evaluation of a new product’s effectiveness is probably changing in the clinic to include some level of cost:benefit evaluation and market researchers should be changing as well to provide the most accurate cost:benefit information to clients.

About the author

Jeremy Smith – Director of Client Strategy, The Planning Shop

Jeremy has over 12 years of global pharmaceutical research experience, including over three years of exclusive oncology experience.

Download the pdf version here.

By Emily South

Whilst many in the Healthcare world have been focussed on the aging population and their effect on hard pressed health providers or wondered how the “have it all” Baby Boomers will react to diminishing personal health – the Millennials have crept up on us. Surprisingly Millennials, born between the early 80’s and the end of the century will soon surpass those Baby Boomers in actual numbers. This younger generation defines itself by the technology advances made by their parents. They see “Technology use” as what makes their generation unique and use their personal digital devices everywhere from the bathroom to the bedroom, in the street and in the office. What’s more they rate a brand or service on its use of technology more than on the brand itself, tending to be introduced to their brand or service via linking, pinning or tweeting information on social media.

So what do pharmaceutical companies need to bear in mind when marketing to Millennials? Here are six insights that can help your brand gain traction with this generation.

Insight one: Provide Millennials with a higher purpose beyond the brand

Millennials have grown up with a bombardment of information; spoilt for choice they have learned to actively filter where they choose to focus their attention and on which device (parents know this only too well). Marketers and their advertising only have a few seconds before Millennials become their biggest fan or pull the plug. So what does this mean for marketers?

Millennials genuinely want to be inspired by brands, so brands need to give something back that will deliver on a higher purpose. Pfizer launched their US campaign – “Because they share”, which encourages young people to take selfies and post them online after receiving their vaccine shot against meningococcal disease B. By tapping into the idea of sharing, which ironically is what puts this group at increased risk of this disease, the product is being promoted, but also empowering patients to educate their peers on the importance of vaccination.

Insight two: Sell lifestyles

Not only are Millennials looking for a higher purpose, they are also seeking out experiences – considering this just as vital as establishing a career. The increased ability to travel more easily and cheaply means Millennials have a new sense of freedom and do not want their health concerns to hold them back. There is significant opportunity for healthcare companies who are able to promote lifestyle services, whilst encouraging proactive engagement of patients in their own healthcare. The NHS in the UK have recently made a move in this direction by collaborating with Pharmacy2U to offer a home delivery prescription service. Hardly a unique idea, but one that will make a significant difference for many patients, and in particular the Millennials, brought up on ASOS and Amazon.

Insight three: Help them find ways to manage the pressure

They are feeling more pressure than ever of ‘emerging adulthood’. Whilst they don’t worry about retirement or the frailty of old age, they are anxious ‘in the moment’. They are concerned about making the right decisions about their social status, career, an affordable home, starting a family etc. In order to make a decision Millennials are happy to spend hours searching online, in order to get it right.

Clearly none of us wish pharmaceutical marketers to exploit this anxiety but rather help create smart tools to support decision making: fast access to the right content and in an engaging, digestible format. An example to follow would be MyFitnessPal, which is the most popular health and fitness app in the world; the app’s database of more than six million foods makes it easy to track your diet, no matter what you eat. Whether you’re trying to lose weight or put on muscle, the app helps determine the best things to eat to meet your goals.

This is the kind of support Millennials value and will ultimately pay back to those seeming to understand their needs.

Insight four: Support a more diverse doctor-patient relationship

The modern doctor-patient relationship is complex and not defined easily, but there is no doubt that patients are contributing to the conversation more than ever. A side effect of this newfound confidence is to question how satisfied we are with this relationship and Millennials will further this trend. Physicians are already prey to subjective online star ratings such as on iWantGreatCare.org, and with the integration of more objective measures such as quality metrics, seeking the wisdom of the crowd will become the norm in order to seek trusted relationships.

Trust, however, is simultaneously going to compete with modern lifestyle demands; for common complaints and short-term illness Millennials will see greater value in the convenience of remote and on demand telehealth. Opportunities exist to continue supporting doctors with this evolving patient conversation and helping the Millennial healthcare professionals find a modus operandi with the Millennial patients.

Insight five: Tap into the social power of online patient advocates

While the baby boomers are sceptical as to whether online information is ‘true’ and ‘trustworthy’, Millennials cite the anonymity and personal stories as key factors that render social media a credible source of information for them. The result: patient bloggers who share their personal story and experiences online have large followings and significant influence over which brands are, and are not ‘for you’ and – in the context of healthcare – which diseases need our help.

Take Stephen Sutton for example: diagnosed with colorectal cancer at the age of 15, Stephen set up his own website and blog, where he posted his ‘bucket list’ of things to do in his final months. His blog created unprecedented awareness of colorectal cancer and within 1.5 years, over £4 million had been donated to a charity funding research into this disease.

Healthcare companies should not only be listening closely and embracing these brave individuals, but also actively measuring and reacting to the market changes they are presaging.

Insight six: Integrate patients (and doctors) in your brand development process

Despite their increased anxiety, many Millennials will trump this with a strong sense of aspiration and a need to do better than their peers; resulting in a strong momentum to improve and innovate. But how can this best be capitalised upon by healthcare companies? Merck took a leap forwards by running a longitudinal patient community alongside the brand development of their new allergy products through to launch. This enabled an ongoing engagement and innovation process, creating a fertile discussion forum for uncovering insights and generative solution building.

With their reliance on technology, their openness to social media, their suspicion of unfettered capitalism and the older generation, the Millennials can appear a challenging audience. But by understanding them, engaging them and cocreating with them marketers will find a willing and resourceful customer base.

About the author

Emily South is the Innovation Director at The Planning Shop. With an active interest in people, stories and ideas, Emily drives new product development for effective pharmaceutical brand building.

Download the pdf version here.

By Caroline Mathie, Rare Disease Group

Caroline Mathie discusses some of the challenges in researching rare diseases, what the broader market can learn from observing these approaches, and the role of online research in particular.

Earlier this year, England’s chief medical officer called for the ‘genomic dream’ of genome sequencing for all cancer and rare disease patients. Accelerated use of genome sequencing is allowing the identification of ever rarer diseases – a recent case in point being six children who were identified through an international database of genes and disease characteristics as having the same ASXL2 gene mutation. This answers two fundamental needs experienced by those with rare diseases; (1) knowing the cause of their problem and (2) the ability to share their experiences with others with the same condition. It also presents the industry with an opportunity to address the root cause of the disease through targeted therapies.

Background

By March 2017, 49.7% of the world’s population had access to the internet (88% in North America and 77% in Europe) – figures that are growing rapidly. Unsurprisingly, this access is a valuable tool for researching rare diseases. In Germany alone, the Journal of Medical Internet Research (January 2017) identified 693 websites containing information on rare diseases, many of them provided by support groups/patient organisations and showed that these are extremely valuable sources of information for patients and their families.

A high proportion of internet users engage with social media, including Facebook and Twitter, and there are many social media support groups for a wide range of rare and ultra-rare medical conditions. As genome-wide analyses, such as exome or wholegenome sequencing, become more commonplace, it is likely that the number of patient groups for rare diseases on social media will increase substantially.

Patient isolation:

Problem and opportunity

Having a rare disease can feel lonely, and rare disease patients are already fighting their isolation through social media, and by linking to others with the same condition. However, internet access also offers new opportunities in terms of specialist consultation, and patient education.

As new diseases are identified, ever more patients are forced to travel long distances for lengthy periods of time to specialised treatment centres. Each new disease may require a multi-disciplinary team, sparking the need for information and education for patients, carers and often other treating healthcare professionals (HCPs).

The use of the internet, to share information and for discussion, has become critical to both reduce the burden on health services and give patients the information they want at the time they want or need it. Forward-looking specialists are now looking at technological advances to enable at least some consultations with patients via video conferencing. However, though they may relieve logistical and time burdens for patients, fears have been expressed that they may be clinically risky and associated with significant technical, logistical and regulatory challenges.

Forums:

Opportunity and challenge

Patient forums are having a dramatic effect on the world of market research. They often emerge spontaneously after a small number of patients set up networks or communities to address their needs for information and to share experiences. These types of forums – and other, more established, groups – have been great tools for market researchers to gather information about the experiences of people with rare diseases, as they allow thorough observations of forum conversations. However, the forums may become hidden, as closed or invitation-only groups, if they become unwelcome targets for pharma and the healthcare industry. Thus, what could have been an opportunity for market researchers can turn into a frustrating difficulty.

Another problem with forums is that the industry itself has ethical and compliance concerns regarding too much contact with individual patients.

Nevertheless, the emergence and growth of patient forums suggest that the fabric of the rare disease market research world may have to change from ad hoc recruitment for interviews to a multiprong approach which includes much longer-term community observation.

Some solutions

All is not lost, however. When it comes to using online forums and communities for rare disease market research, we can, for example, set up our own ongoing network or community. To be effective, this requires knowledgeable and effective moderation – continuously – which is costly.

However, it does provide the ability to address recruitment issues with a specific set of patients and, more importantly, facilitates an understanding of the longitudinal journeys of different patients and their families through listening to their views over time. The community also provides the ability to identify common points on the patient journey and the needs they have and the questions they are asking at each, to build a comprehensive picture of homogenous vs diverse or segmented needs.

Less costly, but effective, is to ask to join the specific closed communities as market researchers. Some forums allow this and some do not.

Patients can also be researched using standard approaches online, which, of course, come with the usual online issues. With rare diseases, questions around patient identification are more significant, as is making absolutely sure the patient really is a patient. Guaranteed security and compliance must also be in place. Finally, if clients are given access to listen to communities, specific patient identifiers need to be removed, and if it is a short-term moderated community, any inputs or questions should not reveal the identity of patients.

Market research – a change in approach

As part of the market research industry we need to explore both a change in approach and, potentially, a change in the business relationship we have with our clients if rare disease market research is to be achieved successfully.

We also need to discuss our approach to dealing with duty-of-care issues up front, if we establish a long-term, moderated community.

Clearly there is also a role for traditional research approaches for these isolated patients using the web, such as teleweb interviews and Skype. Visual connection is also helpful to create rapport and reduce the sense of isolation.

In summary

The market research model for rare diseases is changing and to benefit from the richness of data produced by long-term patient communities, we need to think differently, set up relationships differently and consider not only the market research, security and compliance aspects, but also the ethical duty-of-care issues to sustain communities that may become important components of patients’ lives, especially genuine patients’ perspectives. Targeted utilisation of such insights can bring significant competitive advantage. Therefore, pharma companies should embrace social media listening to help them implement further actions appropriately for greater commercial success.

About the author

Caroline Mathie

Caroline leads the Rare Disease Research Group at The Planning Shop. After studying Medical Biochemistry, she spent 14 years at IMS Health, over 10 years as an independent, director level consultant and four years as a director at J & D Associates. Throughout her career, Caroline has had an active interest in orphan diseases and has expertise in a wide range of orphan disease conditions, including various lysosomal storage disorders.

Download the pdf version here.

As the ophthalmology market becomes more competitive and brands seek successful third-to-market positionings, Portia Gordon and Simon Barnes examine whether learnings from a successful ophthalmology brand launch can be applied to other therapy areas and pharmaceutical brands.

First, let’s consider the two general rules of brand building:

1) No problem, no brand

2) One, two, segment.

No problem, no brand

‘No problem, no brand’ means that, unless a new product is solving a problem (rather than just adding a nice-to-have benefit) for its core customer, it will not succeed.

In general, the most motivating solutions exist for problems that are already known. Occasionally a new product can serve a latent need – i.e. offering a solution to a problem that wasn’t already known but is instantly recognisable when a solution is offered. This is what the iPod did in consumer markets.

Customers can also be educated about unknown problems. However, if these are not instantly recognisable, the company promoting the new product will need to have very deep pockets if it is to succeed in the much more difficult task of creating the new market.

One, two, segment

The average human brain, though containing more synapse connections than there are stars in the sky (estimated at 100-1,000 trillion), systemically avoids complex decision making. This has been well documented in many papers and popularised by Malcolm Gladwell in his book ‘Blink’. For any one decision, our decision-making capability becomes overwhelmed after two choices, which generally means that, after finding two solutions to a problem, we cease to search for others actively.

In simple terms, our thinking pattern can be defined as ‘one, two, forget the rest’, as seen in the vast array of academic literature discussing the ‘Power of Three’ and the ‘Rule of Three’.

Listen carefully, for example, to politicians when they are making a point. The clever ones will give more than two examples and we therefore accept that they are stating a fact that is overwhelmingly supported, and consequently true.

The ‘Power of Three’ leads to a reductive form of thinking where we ‘zone out’ if we have more than two solutions to any problem.

The implication for marketing is that pharma companies need to identify which new problem their brand can solve, and success is only likely when the brand is either the only one, or one of two solutions.

Looking at this practically, it usually means that, if your brand is not the first or second to market, you need to think again.

What if the brand is third to market?

Many brands are not first or second to market, however, so how can a brand successfully launch as the third brand to market? In our experience, if a brand is third to market, success will be greater as a result of segmentation, i.e. targeting either a patient or clinician segment (usually the former).

There is also another strategy; one that states that the third brand to market becomes a challenger brand. If this strategy is adopted, then the challenger brand must solve a problem better than the existing two brands. It can also gain advantage if one of the first two brands to market has been damaged by either efficacy or safety issues, more commonly the latter.

Although few situations qualify for a challenger brand launch – and as a strategy it can often fail – it is by far the most used strategy for third brand pharma launches. It was a strategy adopted by Bayer, for the Eylea brand. (More on this later.)

Why does pharma prefer the challenger brand strategy?

Some senior pharma management teams, without marketing backgrounds, believe that adopting a segmentation strategy would deny the company the opportunity of sales outside the target segments, resulting in missed revenues.

The truth is that, rather than segmenting and owning a place in the minds of a sub-group of patients or doctors, and then expanding into other groups, a challenger brand strategy will rarely gain sales that are more than one quarter of even the second-to-market brand’s sales.

Also, third-to-market challenger brands will often compound this problem by being a challenger based solely on price, not only reducing profits, but still not achieving more than a quarter of second-to-market sales.

Look at third-to-market proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in reflux, third-to-market erectile dysfunction (ED) treatments and third-to-market anti-tumour necrosis factors (TNFs) in rheumatoid arthritis. These examples demonstrate a failure to capture more than a quarter of the market upon entrance and have not truly displaced first- or second-to-market competitors.

Eylea – learning from successful launches via challenge in ophthalmology

Challenger brands can work, though, if the circumstances are right. Consider ophthalmology (specifically wet age-related macular degeneration [AMD], the leading cause of age-related blindness) and the third-to-market launch of Eylea as a challenger brand.

At the time of Eylea’s launch, the market comprised laser-activated photodynamic therapies (PDTs) (e.g. Visudyne), and anti-VEGF’s Lucentis, developed and marketed in the US by Genentech and marketed in the rest of the world by Novartis, and off-label Avastin (developed by Genentech).

Lucentis dominated the market and was – and is – well respected for innovation. Lucentis’ position was, however, weakened because of its association with Genentech and its resistance to gaining a licence for Avastin. Both of these points left doctors in the awkward position of not wanting to take the risk of off-label usage to gain the benefits for their patients (and the health service) of the much lower cost treatment of Avastin.

Consequently, the normal two-brand stranglehold was significantly weaker in wet AMD, which left more room for a challenger brand.

Bayer, with less experience and fewer credentials in ophthalmology, decided, nevertheless, that the market had one strong and one weak brand and therefore it could successfully challenge the Lucentis/Avastin dominance with Eylea, given the Avastin brand weakness.

A launch ensued, which focused on Eylea’s non-inferior efficacy and safety compared to Lucentis, and differentiation due to its every-other-month dosing and dual MoA (trapping mechanism binding VEGF-A and PlGF). This positioned Eylea as a convenient solution compared to Lucentis.

Bayer gained a brand share of 32% for Eylea, which is much greater than the usual 25% for a second-brand share. In fact, Eylea’s strong sales trajectory since 2013 has established Regeneron’s strong position in the US ophthalmology market – its only marketed brand in this therapy area. Eylea’s broad indication, as well as current phase 3 trials in diabetic retinopathy without DME and phase 2 trials in combination with nesvacumab for wet AMD and DME, will probably ensure an unabated sales increase.

The moral of the story: what can we learn for other therapy area brand launches?

First, in certain circumstances it is beneficial, when third to market, to launch as a challenger brand, rather than based on segmentation. These circumstances are defined by one of the two dominant brands having a weakness – in the case of the AMD market, these were: being unsupported and having some negative emotional connections.

Second, the weakness does not necessarily need to be targeted directly. Eylea made its superiority case by targeting a different problem, that of convenience, rather than by positioning itself against a specific Lucentis weakness specifically.

The moral of the story for pharmaceutical market brand launches is not to try to be a David and take on a Goliath unless you are supremely confident that you are fighting from a good vantage point and you have clear evidence of your opponent’s weakness.

In other words, become a challenger brand – like Eylea – only if you can solve customers’ problems significantly better than the two dominant brands. If not, launch with a segmentation strategy instead.

About the authors

Portia Gordon PhD is Research Director at The Planning Shop. specialising in US and global qualitative market research. With a background in molecular pharmacology and biochemistry, she has over 17 years’ experience in pharmaceutical marketing research. Portia has an active interest in engaging patient participation to educate patients about therapeutic breakthroughs in medicine, and is part of the company’s patient group team.

Simon Barnes is Research Director at The Planning Shop with a focus on market research in the UK, covering all therapeutic areas. He has worked in pharmaceutical market research for over 20 years across several different therapeutic areas, including eye care in an international role. He leads the Ophthalmology Business Unit alongside his UK-specific role.