Who is the final decision maker about your health, when it comes to choosing the treatment you should receive?

Published on 14 Jul 2018

Jeremy Smith, Director of Client Strategy in the Oncology Research Group at The Planning Shop explores answers to these questions.

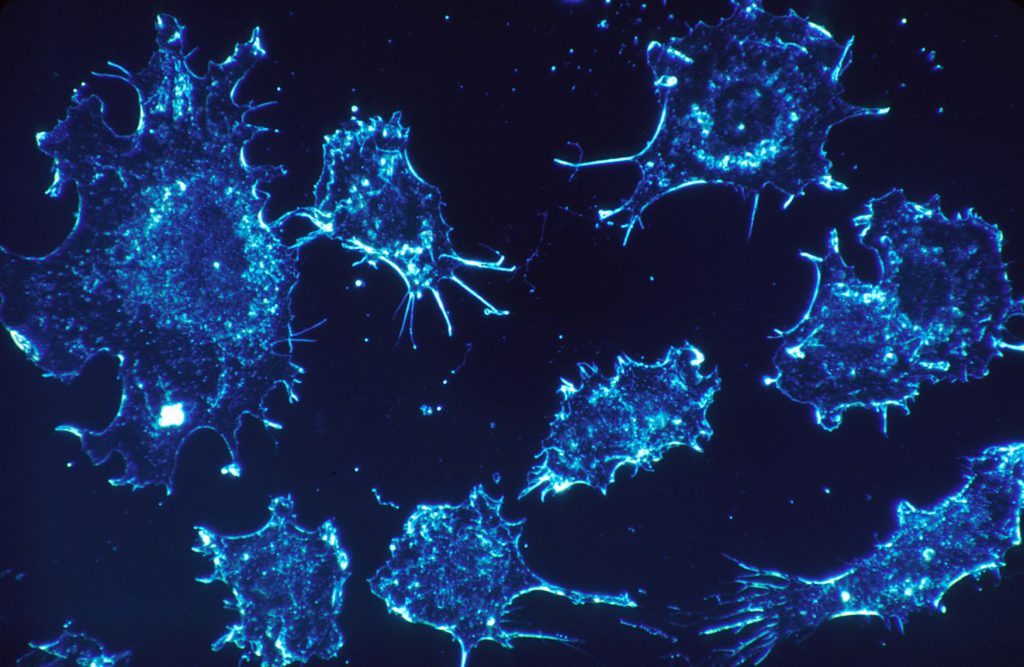

Cancer: One of the worst diagnoses a person can receive, which affects not just the patient, but also the wider family unit, caregivers and healthcare providers.

All these people play significant roles in trying to make the patient well, but how big should these roles be when it comes to decisions, and who should have the final say? Also, what are the implications for pharmaceutical market researchers?

Before we look at the role of each stakeholder, it’s important to highlight the significant advancements in the treatment of cancer – both in the treatments themselves and in patient/caregiver knowledge.

The past and the present

In the not-so-distant past the only treatment option for many cancer patients was systemic chemotherapy. More recently, immunotherapy has significantly changed how we treat a wide variety of malignancies. Nivolumab, the first FDA approved checkpoint inhibitor was initially approved for the treatment of Melanoma in 2014. Since then, checkpoint inhibitor approvals have exploded from several manufacturers in multiple tumor types.

Whilst the treatments themselves were advancing and immunotherapy has drastically changed the treatment options, so too were the education resources that were available and targeted to patients and caregivers. This has led to the evolution of the informed patient, which has drastically changed how treatment decisions are made.

How have patients become more informed?

Advertising

The first pharmaceutical television advertisement aired in 1983. That advertisement was for a prescription ibuprofen and was sponsored by Boots Pharmacy. Despite this early 1980s commercial, television advertising did not catch on until 1997 when the FDA ruled (after the 1996 Shering-

Plough Claritin television commercial) to relax the guidelines for television commercials. Television advertisement spending then jumped from $12 million per year in 1989 to $1.17 billion in 1998 and it has continued to increase ever since with spending in 2017 totaling $3.45 billion.

Although some question the ethics of pharmaceutical DTC advertising, there is no doubt that it has contributed to the increase of more informed patients and caregivers. Despite the marked increase in pharmaceutical DTC campaigns, there have been few television commercials for oncology treatments and, those that did exist, focused on supportive care rather than cancer treatments themselves. Still, the effectiveness of pharmaceutical advertising cannot be overstated. For example, prior to the Procrit DTC campaign, the drug – approved for certain types of anemia (which can cause patients to feel fatigued) – garnered little use because patients were not telling their doctors they were fatigued. The Procrit DTC campaign however, empowered patients to talk to their doctors about their fatigue which resulted in a significant increase in Procrit prescriptions.

Fast forward to 2018 and the number of oncology treatment television DTC campaigns are increasing as we see more and more advertisements for anti-cancer medications in the United States. Television campaigns currently include nivolumab, pembrolizumab and even reach beyond checkpoint inhibitors to include palbociclib and abemaciclib. These commercials are likely to be raising interest and awareness among patients and caregivers, causing them to do more research about their condition and possible treatment options.

Digital transformation

Beyond DTC advertising, and the availability of disease and treatment information, patients are increasingly able to take advantage of new technologies to access and monitor their own health information via online portals, wearable sensors and smartphone apps. As Eric Topol points out in his book ‘The Patient Will See You Now’, while we’re not fully at the point of the patient owning their medical records, the technology exists, and this reality may not be far off.

So, what does it all mean?

Ultimately, it means more informed patients and caregivers, with physicians no longer being the sole providers of medical and treatment information. Patients and family members are becoming self- educated about their malignancies and treatment options, resulting in all parties having strong ideas about the best treatment option.

Let’s look at a typical scenario

A newly diagnosed lung cancer patient goes into their oncologist’s office accompanied by their adult child.

The patient has seen the nivolumab and pembrolizumab television commercials and has completed extensive online research that has resulted in her believing that immunotherapy is the right choice for her because it provides a good chance for prolonged survival with minimal side effects.

The adult child, having completed similar research, believes that immunotherapy + chemotherapy is the right choice since it combines both treatment modalities and should, therefore, provide the best chance at survival.

The oncologist, utilizing all of his extensive medical training and experience, believes that standard chemotherapy is the best first choice in order to save immunotherapy for second line. In this scenario, who has the final say? What will the treatment choice be?

This answer will of course differ for each conversation, but it is safe to say the final decision will be mutually agreed upon. The oncologist would be remiss not to consider the patient’s wishes

and, most importantly, the reasons behind those desires. But similarly, the patient would be remiss to dismiss the wishes of their family and the extensive experience of the clinician.

What does this mean for pharmaceutical market researchers?

In the past, most pharmaceutical market research projects have been conducted around physicians, payers and KOLs with the patient perspective often relegated to a singular patient journey project. However, as treatment decisions are becoming increasingly more collaborative, it is important to include the patient and caregiver perspective in pharmaceutical market research projects to build stronger brands. Two key brand rules explain how this can be done.

1. ‘No problem, no brand’

Ultimately, the brand needs to solve a problem in order to be successful. By incorporating the patient and caregiver perspective, market researchers are better able to frame the problem that the brand will solve. Even if the overall plan does not include a DTC campaign, what better way to bring the problem to life than to incorporate the patient language and perspective?

2. ‘The truth, powerfully told’

The inclusion of the patient and caregiver perspective serves to strengthen the overall brand story. The underlying reason many HCPs enter medicine is to help people. How better to tell a powerful, motivating story than by incorporating the perspective of those patients who will be helped by the brand?

That’s great, but how do we do this?

It can be easier to include the patient perspective than one would think! Often times, KOLs are included at the start of a project in order to get the thought leader perspective on the future treatment landscape or the merits or a particular product.

Why not take a similar approach with patients and caregivers? Including a few patients and caregivers in order to get their perspective about the challenges of living with a condition or taking a particular medication can pay significant dividends. Even if the brand never plans for a DTC campaign, this additional insight will strengthen the HCP-directed communication materials. Imagine how much more powerful the HCP directed messages or concepts would be if they included the very language that they hear from the patients they are treating!

In conclusion

Traditionally, the incorporation of the patient perspective would mean a ‘patient journey’ project. While a traditional patient journey can certainly

be useful, in an age where patients are more knowledgeable and empowered, we suggest going beyond the traditional approach. Consider including patients and caregivers in other, typically HCP-only, projects as well. The patient/caregiver perspective should be incorporated when developing a positioning, identifying drivers and barriers to use, and creating physician directed messages, just to name a few.

About the author

Jeremy Smith, Director, Client Strategy

Jeremy has over 12 years of global pharmaceutical research experience, including over three years of exclusive oncology experience.

Download the pdf version here.

)

)

)